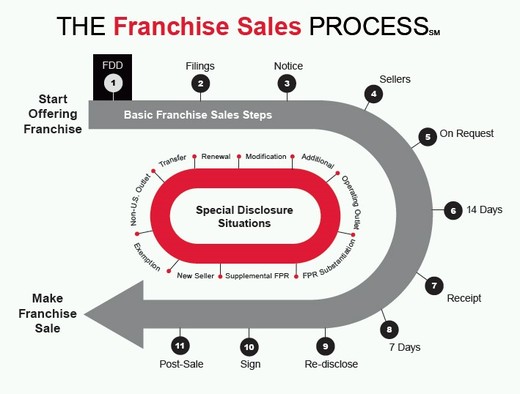

This article deals with compliance with contract issues, not compliance with laws regulating franchise sales. Its opening major premise is that the concept of compliance has many dimensions, is seen from many different perspectives, and is in many instances more situational in its relevance that an institutionalized constant.

I don't mean to be flippant or casual when I suggest that compliance is a sometimes thing. The fact situations in which compliance becomes a do or die issue so often involve application of compliance standards in one situation that are not utilized or insisted upon in normal situations, that a legitimate question arises regarding selective enforcement.

Sometimes selective enforcement is justified, as in the case of a hard core recidivist constantly resisting conformity.

And, as the trial lawyers (myself included) so often say, that makes for the 'justiciable issues' revenue stream we know and love so well. It becomes in most instances a question for the trier of fact, judge or jury, whether the behavior of the parties in this particular case is acceptable, or aberrational and without just cause (whatever that means).

The general rule of contract construction is that the express terms are there for the purpose of being insisted upon. That's too elementary to be of much assistance in understanding how the contract language and the franchising agenda work together. It's one thing to be able to read and quite another to understand the 'system'.

But that's what you agreed to, so that's the standard to which you will be held, unless of course you were induced to sign the contract by misrepresentation and can prove that.

Stupidity/ignorance is not a defense, but it is still unlawful to cheat the stupid (in most states).

General rules of construction, however, are themselves subject to selective application when the ambient circumstances suggest that to do otherwise would work injustice. One important point is that whenever a variance from strict compliance is in order, the contract is written so that it is the franchisee's burden to prove that it is in order. That fact alone gives the franchisor most of the options in deciding what level of compliance may be insisted upon in any individual situation. Inasmuch as the franchise contract is written to give the franchisee the fewest possible options in time of trouble, reading the contract does not inform a potential franchisee of the 'quality' of the investment being offered.

A potential franchisee has to start out with the understanding that the contract favors the franchisor at every turn and on every question. With that level of riskiness staring you in the face, the due diligence on the quality of the investment being offered is the most critical area of inquiry. Unfortunately, new franchisees almost never go to a franchise industry specialist for that due diligence. They go to their cousin or their divorce lawyer who has absolutely no ability to inform them about what they are getting into. Is it any wonder that about 70 % of them go broke in the first three years?

What the International Franchise Association says about survival chances being enhanced if you are a franchisee is thought, by many who have good reason to know, not to be true. Judging the prospects of the newer franchise offerings by the success track of the more mature franchisors is not a reliable risk assessment technique.

There is a curious analogy that I often joke about (See 'The Ultimate Franchise' at www.SeamusMuldoon.com ). Most of us casual compliance folks think of the fundamental mandates of the Bible in terms of the Ten Commandments, supposedly a contractual construct given by our Creator and accepted by the Israelites at the theophany on Mount Sinai. Like the Sherman Antitrust Act, the Ten Commandments have sufficient constitutional vagueness to allow them to be interpreted and applied to the ambient circumstances of an ever changing world.

The more compulsive amongst us have, however, scoured the Bible and found at least 613 commandments. People like this write franchise contracts. Compliance with 613 commandments requires the dedication of life itself to compliance, with little time or energy left over to do much else. Franchise contracts are so convoluted, especially when viewed in conjunction with franchise operating manuals, compliance with which is mandated in all franchise contracts, that running a normal business can be obstructed rather than facilitated by over zealous devotion to compliance. Where is the line to be drawn that demarcates reasonable compliance from fanaticism? The answer is that it is an ever moving line.

This article is intended to suggest an approach to how to find the line in the particular situation that you face today.

A franchise contract is written to cover every conceivable situation and to maximize the likelihood that in any dispute the franchisor will have the upper hand. Those of us who draft franchise contracts have been fine tuning every provision and adding provisions over at least the last 40 years since I have been in practice to keep the advantage as far over in the franchisor's corner as possible through changes in statutes and regulations and to accommodate the variant approaches to dispute issues that have come out of court decisions and opinions.

It requires constant vigilance to counter any change that might erode a franchisor's control options regarding the franchisor's name, system, identity and the enforcement of the franchisor's will in all situations.

Because the franchise contract is written to be the ultimate safety net to enforce franchisor control options, no matter what, it may not be/is not correct to think of it as the standard for normal day-to-day operations. It deals with emergency preparedness, and emergencies simply do not occur all the time. In some companies it may seem like emergencies occur all the time, but those are not system wide emergencies unless the company is not competently managed.

There are usually different emergencies amongst many franchisee scenarios. Even the operations manual, which is supposed to be the micro management reference source, is a 'best case' construct that itself changes several times each year. What does not evolve does not survive. Once protecting the crown jewels is accounted for, no one wants the documentation to stifle progress.

The contract itself is not the crown jewel. The business relationship and its prospects for success and growth are the crown jewels, and the contract is to serve that, not to usurp that -- no matter what lawyers think.

I submit for the sake of this argument that in a well run organization, on a day-to-day basis, neither the franchise contract nor the manual is fully observed/complied with.

They are target benchmarks that are rarely/never one hundred percent met in a well run business that is making money.

Technically speaking, therefore, there is non-compliance/breach occurring every single minute of every single day.

And in a 'management by exception' mode, what we do is react to activity that it outside the margins of tolerance and perceived to be pernicious. Outside the margins of tolerance and not perceived to be pernicious is called innovation. Innovation, once field tested, is brought into the tent and becomes part of the operational fabric.

Given that 'breach' is always occurring, one must then, I think, concede that the critical talent that must come into play in any enforcement decision is management discretion.

As we say in Texas, that's why they pay us the big bucks -- to use excellent management discretion, to be able to balance competing interests and prioritize issues so that the best result with the least adverse risk becomes the most likely outcome in any situation.

There are limits on discretion. What one might wish to do in a seemingly deserving situation is sometimes influenced by considerations of precedent. What might be a salvaged relationship is sometimes lost to considerations of precedential impact, and more frequently lost to management ego issues.

Here is where a great deal of error creeps in, as many situations feared to be precedent setting are actually not precedent setting. Competent analysis is required to distinguish between the two. If I let this franchisee off the hook on this default, everyone will think they can get away with it too. Even though there is no regulation or law that requires uniform enforcement of any contract provision, there are erosion and dilution issues that can become acute if the perception amongst the franchisees is that the franchisor is not militant about enforcing the franchisor's rights and authority.

Rabble rousers are all too frequently looking for some wiggle room to find issues to use as rallying points to promote the formation of adverse constituencies around some agenda or other. And sometimes there is a situation in which tolerance should be exercised, especially if the franchisor is not blame free. Confrontations over enforcement issues that end up in court/arbitration and that go against the franchisor become worse precedents and more virulent in their impact.

The nature of the event(s) of compliance failure, the level of gravity, is always the first step in the process of trying to decide whether to actually declare/give notice of a default under the franchise contract. The second step is due diligence. All too often the second step is ego driven/agenda driven rather than objective investigation. That's a wrong turn in practically every instance. It matters much less who is in issue here than the ability to provide adequate documentation of the default, including the ambient circumstances leading up to the default. Files must be marshaled, people interviewed and statements taken and signed.

This is lawyers' work. If management does the interviewing, there will be more concern on the part of the employees being interviewed that they respond in harmony with what the think the boss' agenda is rather than a straightforward fact statement. That concern will be there even if the lawyers do the interviews, but it will be much more palpable if the executives do or are present during the interviews. Even with the lawyers doing the interviews, it is often the case that the employees have met to assure that they are all on the same page, and sometimes there has even been a meeting with the boss where they are made keenly aware what the boss' agenda is. The employee may give false statements effectively while on his home turf with wishful thinking friendly folks in the room. He can't reliably be expected to do as well under cross examination by opposing counsel with unfriendly folks in the room and a transcript being made that can be evidence of perjury. This is the very essence of ego driven procedure, and the worst possible scenario for the production of a high quality result. When you impair the quality of your own company's due diligence, bad things happen. I ought not even have to say that. But I have seen so much of it that in my opinion it merits comment. But this article really isn't about the ego driven boss. After the facts are marshaled and able to be examined in a sensible mode, then agenda can rationally come into play. Having an agenda isn't bad per se. Letting the agenda get in the way of accuracy is very often extremely bad in the results obtained. If the agenda is a constructive agenda, accuracy won't dilute it or thwart its advancement. You really can't have an agenda that depends for its effectiveness upon management never making mistakes. Management is human, and mistakes will happen. The agenda must work despite management mistakes if it is a positive agenda, a substantive (non fluff) agenda.

The vast majority of compliance failure is dealt with at the level of the inspection report. In a well run company, copies of inspection reports are left with the franchisee at the end of the inspection visit, after discussion with the franchisee/manager of what inadequacies were found. If the problems were more than marginal, there may be a follow up inspection at an earlier date than would normally occur to be sure of cure or a detailed written cure report required of the franchisee. If people are using good sense, it ends there. If people are not using good sense, deficiencies persist and may get bucked up to operations and an operations manager may call or send an email to the franchisee requesting an explanation of why 'stuff' wasn't fixed when it should have been fixed. If compliance failure continues and the problem is significant, the director of operations will usually make personal contact to inform the franchisee of the risk of default notice, and ask if there is some agenda at work that is making the deficiencies persist. This makes good sense and it makes for a good paper trail to show a judge or jury that the franchisor is really trying to be as reasonable as possible before whipping out the big gun. Persistent compliance failure always gets more aggressive treatment in court than occasional events of compliance failure. Only the persistent failure gets the big gun treatment unless the nature of the event is such that there is an emergency need to take immediate remedial action. This is the regime for dealing with operational defaults, and I have seen CEO and COO type people get on the phone personally before resorting to the heavy hand. Default notices usually need to be approved at the top anyway, even if the honcho does not insert executive authority into the mix -- sometimes because the executive really doesn't want to be a witness if that can be avoided. Apex witnesses are a phenomenon to be avoided. They frequently make terrible witnesses, and often judges and juries simply don't buy the notion that the executive really doesn't get involved personally in the day to day operations. The Enron executive is the worst case scenario for this problem.

Above operational compliance failure would probably be financial defaults. Things don't get paid when they should get paid. This is more serious than not putting date labels on the inventory in the walk in cooler. This also goes to another part of the franchisor organization, the accounting and finance people, who should be less tolerant than operations people. Financial compliance failure is more frequently a harbinger of greater and more fundamental failures of compliance, and if they are not nipped in the bud, blossom very quickly into situations requiring surgery.

This is dealt with more effectively where the franchisor is professionally managed. When the founder is still at the helm, the franchisees are often seen as his children, and too much forgiveness of tardy financial compliance leads to systemic evils of enormous proportions. Allowing franchisees to fail in compliance with financial responsibility issues is never beneficent. Immediate resolution is the best resolution. The issue should get kicked upstairs sooner, and executive approval of default notices should be given after one attempt to find out if some emergency/calamity has befallen the franchisee that might justify exceptional consideration. The recent hurricane season on the gulf coast and health calamities epitomize the level of calamity called for. The level of clemency allowed will fit the particular situation.

If it is not done in this sanguine fashion, it is always the case that the slow paying franchisee starts to feel that the need to account and to pay up is not acute. The obligations to the franchisor go to a lower order of priority. Even in the normal pecking order of things, paying the franchisor is all too often on the lowest rung after all other expenses of operation. The psychic influence always buried in the mind of the franchisee is that the franchisor doesn't deserve to be paid if profits are down, regardless of the reason. If you don't kill this germ immediately, it grows into a monster. Franchisors who, absent calamity, allow franchisees to sign promissory notes for past due obligations are not helping anyone. The more the franchisor relents on financial performance, the worse the situation will always become, until ultimately the franchisor has a drawer full of promissory notes that are of dubious value and the auditors make you take a write off on your operating statement and balance sheet. Shame on you if this ever happens. And if you let people give you promissory notes instead of cash, you deserve what will happen to you. This is not a legitimate form of kindness. The franchisees who owe you money will eventually try to find a way to get out of paying you. The more of them who owe you money, the more enticed they will be to share costs of litigation, and the more prone they will be to foment any kind of problems within the system. This kind of kindness never goes unpunished. Any CFO with promissory notes in lieu of cash needs to be relieved of duty. If the founder owns the company and wants to throw away his/her money, that's their business. In a professionally managed company that is per se incompetence. And they brag about not paying you to each other. That leads to 'why should I pay if Charlie aint paying?' How far do I have to go on this scenario before the point is made?

The other category of defaults, neither operational nor financial, fall under the heading structural compliance failure. This includes using the name/mark in an unauthorized manner, establishment of unauthorized stores (almost always accompanied with under reporting of sales and royalties), unauthorized assignment of the franchise.

Hijacking the franchisor's identity is rarely other than intentional. Someone would have to make a clear and convincing case that is almost impossible to make to explain away anything like this. Every now and then, a franchisee who sees termination coming will find a sucker to dump it on, getting cash money at closing and hitting the road. Sometimes the sucker is really a bumpkin with money (like an immigrant) or just an opportunist. The immigrants with money may not be money bumpkins, but they are often bumpkins when it comes to how franchise assignments work. Part of this is simply that they come from countries where business is simply not done this way. Many come from cultures in which without deception it is impossible to get anything done. Bribery/extortion is so pervasive that open disclosure is suicide. I have seen many of these situations in real life. In one an established franchisor bought a major market from an area developer who had just received notice of termination of the area development agreement for failure to meet the development schedule (and who had no hope of meeting it with a reasonable extension). He bought it for cash. He did no due diligence. The deal just seemed too good to take any chance that it would get away. The buyer then called the franchisor to introduce himself as the new owner of Detroit, only to learn that the rights he just bought for cash had been terminated. He should have known better. He was impulsive about many things. If his gut told him it was a good deal, he went for it. I had to bail him out of several deals in the middle of the night over the phone from some long distance venue. Years before that, he had been talked out of the opportunity to buy Michigan from Colonel Sanders (by a lawyer who said it was a scam) when the Colonel was just getting started. He hated lawyers. He vowed never again to miss out on grabbing the gold ring. How he had gotten to trust me and start calling me first at the last minute before writing big checks is just good luck on my part, I guess. He was a sucker for any fried chicken deal.

When he learnt he had been bamboozled out of big bucks for the Detroit rights to a very hot franchise name, he called me and, with murder in his heart, ordered me to get injunctions and tie everybody up in court until they begged for mercy. As we had no case against anyone against whom a judgment might be helpful, I infuriated him all the more by telling him that was not the way to approach this. I suggested begging. He blew his stack. He was not a beggar and no one was gonna beg on his behalf. When I explained to him that all he would do by going into court was make a public record of his own stupidity, and that he would become the butt of franchise jokes all over the country for the next five years at least, he started to calm down. I learnt that I am really a wonderful beggar. We flew to the franchisor's office, met with the right people and walked out of there with a 40 store market worth of franchise rights. Maybe that's why he called me whenever people offered him the moon after a big dinner with cocktails, wine and after dinner drinks.

I have had a few immigrant situations also. Many immigrants with a lot of money have very poor insight into the intricacies of how franchising works. Many come from environments/cultures in which concealment and devious business behavior is considered to be the only way to survive. They bring these perspectives with them to every deal. Frequently they view contract signing as theater. They know how to act out the part, but have a non-compliant agenda. They would not hesitate to rip off their own countrymen, and certainly would not hesitate to do the same to a stranger. Only in recent years has franchising really made big inroads into many areas of the world other than the European Union. Pre-contract execution cultural conditioning helps a lot. You owe it to yourself to inform the potential immigrant franchisee that your contract is not a social document and that you will police compliance. That should be done in addition to the formal franchise contract language that, of course, says it will be done, but says it in lawyerese. At every franchise sale closing event there ought to be a 'Come to Jesus' discussion in which the franchisee-to-be is told rather frankly what compliance is going to be like in reality. There are a number of steps that could be taken at the closing event that could make life a great deal easier for franchisors when trouble raises its ugly head.

Franchise transfer is one of the events in which the franchisor's compliance expectations often have little to do with the seller's intended course of action. Sometimes, if the seller of a business is one of their countrymen, the greenhorn wrongfully assumes that some trust ought to be extended. This is what a crook trades on. They buy rights that a seller has no authority to sell, for cash of course. The seller hits the trail back to his homeland and finding the money is hopeless. The franchisor has the unpleasant task to tell the buyer that he bought nothing. In most of these situations, but not all, the only way to approach the nightmare in representing the buyer is expert begging. Hopefully the buyer has good business credentials of some kind that may suffice to convince a franchisor to accept him and make the distinction between the sucker who got scammed and the person who scammed him. Hopefully also, the buyer really is someone who was actually taken in, and not an active co-conspirator in a scheme to hijack a franchise.

Probably the main obstacle to be overcome in this scenario, assuming that the buyer would be a good operator and can handle the responsibility, is that if the franchisor rejects the buyer as a potential franchisee, the franchisor then has a profitable store that has now become a company store that the franchisor can sell to a new or old franchisee for its going concern value, without itself having to pay going concern value to get the store. The sucker who bought from the non-compliant franchisee is out all his investment, and the franchisor will get the going concern value if it refuses to accept that person as a new franchisee. The franchisor may not have ripped the poor bastard off in the first instance, but the franchisor will end up receiving the fair market value of this going concern by refusing to recognize the duped buyer as a new franchisee (assuming the buyer is willing to sign a then current franchise agreement). The attractiveness of that windfall is sometimes more than a franchisor can resist. Not at least allowing the buyer to sell out and recoup his investment could be viewed by a court or jury as an actionable form of over reaching, assuming that there are other operative facts that weigh heavily in favor of the buyer as a competent operator. The situation is too easily portrayed as plain old greed. Does the franchisor have the right under the applicable contract documents to do that? Of course it does. But the buyer may not yet be a party to such a contract, and the contract escape mechanisms may not apply to a buyer who has not yet been approved. That's why being able to perceive the difference between the duped buyer and the swindling former franchisee who sold the business improperly may in the long run be something worth consideration. It isn't really giving away/making gifts of corporate assets when a franchisor decides to accept the buyer in such a transaction. It's a legitimate officer's bona fide judgment call about what is the best business practice in any individual situation. Doing it does not set a precedent that could be used to require that the same be done for every unauthorized buyer. It depends upon the circumstances in each instance.

These are always cliff hangers. The situation gets sorted out very fast once the franchisor realizes what has happened, but there are several days and nights of sheer terror. The Buyer usually has everything he owns in the world tied up in this transaction and will lose his home and have to enter bankruptcy. His entire positive business history will be destroyed in a flash if the franchisor cannot be convinced to give him a break. The franchisor has to get really good results from investigating these deals to even think of the possibility of giving these folks a break. Even something like the buyer's ethnicity can work against him. Having to get a 'pass' for someone in that fix who is from the Middle East or Russia is a much tougher road. Feelings just run higher against them. There is a definite angst about whether an intentional hijack really is happening. [Cross reference 'Infiltration of Franchise Systems', another in this series of Specialized Tutorials] Even the slightest threat of litigation by the buyer is an act of suicide. Save the threats. If the deal goes south in its entirety -- the buyer isn't even allowed to sell what he bought to save his investment -- you sue if you can find something to sue about. But you never talk about it. You just do it when the time comes. If you know what you are doing and have a decent litigating reputation, the franchisor knows what's coming if some way to 'work it out' can't be found. There's no need to talk about it.

Before I will agree to be the beggar, I do my own investigation. I think that my reputation has some weight in the process. I never misrepresent and I make full disclosure up front so that the franchisor's investigation will not uncover anything I haven't already disclosed. I have to disclose the good, the bad and the ugly -- no one is all good all the time. If I can satisfy myself that my client is deserving of some consideration, then I think I can do a better job for him. If I don't believe him, why take his money and fake it? I won't be able to help him and it will hurt my own reputation. And if the client isn't fully forthcoming with me, this approach will certainly sink his ship. I tell them that so that they will come clean to me. If they don't, they are very likely to get caught, and their investment goes down the drain. So far, my reception by franchisors in these situations has been very positive. I don't always get what I hope for. Sometimes it just isn't in the cards. All too often I get the client after his so-called regular lawyer has done all the wrong things and the whole situation has become acrimonious. That's hard to overcome. People always seem to start out on any tough problem by calling each other awful names. That's really stupid.

This tour of default management issues is certainly not encyclopedic. Even if it were, someone will think of something new next week, and there will be more fodder for litigators. And there are, of course, many flavors of compliance failure within each of the major categories I have suggested.

There is one universal constant in the resolution of all this. If the decision is made to forego terminating a defaulting franchisee, the franchisor should always exact a quid pro quo.

If you have the right to send a termination notice, but opt instead for a peaceable resolution that leaves the offending franchisee with his investments intact, get the benefit at least of an acknowledgment that from that moment on you are free and clear of any claims against yourself. Get a bankable status of effectiveness confirmation. Don't let someone off the hook who may be saving in his back pocket a claim that was about to be asserted against you in the event of confrontation. In commercial leasing this is known as an estoppel certificate. In franchising, I call it a reaffirmation and ratification (ReRat). This agreement says that the franchisee acknowledges that the franchisor is foregoing the exercise of enforcement rights under the franchise agreement; that the exercise of enforcement rights by the franchisor would be a reasonable and proper act under the terms of the franchise agreement; that in consideration of that forbearance the franchisee acknowledges that the franchise agreement(s) is/are in full force and effect in accordance with the written terms and that the franchisee has no defense to the assertion by the franchisor of any term of the agreement; that the franchisee is not aware of any claim that it has against the franchisor, and none are under consideration that have not already been asserted; that the franchisee releases and waives any and every claim that it may have against the franchisor, of any kind or nature whatsoever, whether known or unknown; and that the franchisee hereby ratifies the franchise agreement and all other agreements in force between the franchisee and the franchisor, including any related entities. Be aware that in some states a release of unknown claims must be separately stated from a general release, and put a separately stated release of unknown claims in every ReRat agreement.

Let's shift gears for a moment to another compliance dimension. There is a point at which, no matter how one sided a franchise contract may be written, the franchisor's own exercise of its perceived prerogatives may be sufficiently extreme that franchisees look for ways to 'get even'. Every industry has this experience where the basic protocol of the business relationship is extremely one sided. The insurance industry is an example of this. The practice takes the form or reducing the number of items included in the franchise package without additional charges being made for them -- adding 'fees' for what used to be compris -- or adding non-essential services as compulsory items and tacking fees on for those. In this second category, I include items that may already be in the package and that the franchisees purchase from unrelated vendors, but requiring that they be obtained from a new and related entity at a higher price without improvement in quality. My most recent exposure to this phenomenon involved electronic in-store ambience systems that suddenly have to be purchased from the relative of an officer of the franchisor for substantially more than was paid in an open market transaction. This was also done in a very heavy handed manner. The officer's relative didn't even have the grace to provide a reliably working product or reasonable tech support when it didn't work. New store opening approvals were delayed if the system was not up and running, and many times the delays were due to poor response to technical support requests. When franchisees refused to pay for systems that were installed but not operating, the late payment became a cause for denial of store opening approval and for notices of default being sent out by the franchisor. It was an episode right out of 'The Sopranos', except that it was really happening to people. While this may seem an extreme example of morale destroying avarice on the part of the franchisor, it serves the purpose of demonstrating the kind of franchisor action that causes compliance morale to go into decline. That these actions tend to stack upon one another as similar opportunities to impose additional charges/revenue streams arise should not come as a surprise to anyone.

When the franchisor is doing these kinds of things, it usually is accompanied with programs of 'cheerleading' propaganda about the quality of the relationship and the opportunity. This is seen as utterly venal and cynical, and never has a morale boosting effect. Baloney is always baloney, no matter how you slice it. An excellent example of this kind of baloney is the recent General Motors advert campaign. While its competitors in Europe and Japan are producing better quality vehicles and eating General Motors' lunch out in the market place, GM elects to produce the same crapola products year after year and ride its market share and financial performance history into the toilet. The advert campaign proclaims that 'We are professional grade people'. The obvious absurdity of it is that all those professional grade people at GM can't produce reliable vehicles that can be sold at a profit. DUH! When the message is ridiculous, the relationships to which they apply can't really be expected to improve, can they? This is a B School case study for corporate stupidity. You might as well hang out a sign 'Company In Deep Trouble'. Who thinks up these ridiculous campaigns?

When any franchisor looks at compliance, neglecting to do an examination of the extent, if any, that things being done by the franchisor may be contributing to compliance problems will always produce skewed/unreliable diagnostics. In psychology it's called being in denial. Denying the obvious never produces a cure, does it? I fully understand the temptation to engage in piling on of non-essential items as a way to enhance financial performance, It's not really unlike a person who decides that he likes Martinis and drinks more of them every day than he did last year, while denying that he is becoming an alcoholic. Looking in the mirror isn't always pleasant. But if you dont look, how are you going to know what you look like? 'Nuf said?

Ultimately I must add a disclaimer. This is not intended to be legal advice to any company or person upon which they may rely in resolving or evaluating any claim or event. Each situation you encounter that may involve the assertion of contract rights and invocation of remedies requires that you consult with a competent attorney to assist in the evaluation of that specific situation. Sometimes the decision whether to go forward turns on the personalities of the people involved. I know that doesn't sound right, but based on my experience it is right. Much more is involved in making enforcement decisions than just a technical legalistic sorting out of rights and wrongs.

via email to

via email to