Franchises are mostly created or started by a single founder.

The founder faces an interesting strategic challenge in persuading enough franchisees to voluntarily pay for & add value to the franchisor's property - the franchisor's trademark and confidential information.

1) If enough do, then we will all be better off because we have formed a brand.

2) However, some will not live up to the brand's standards and free-ride on the brand's reputation.

If enough of us expect that others will free-ride, we won't live up to the brand's standards either.

The brand may just flounder along.

(This type of problem is known by many names: social dilemma by social psychologist, the collective action problem by game theorists, the social contract by philosophers, the buy-in problem by management theorists, and the tragedy of the commons by political theorists. )

What sort of personality gets the job done?

How does the franchise system get buy-in from the franchisees? What happens when the founder leaves the system?

How does the franchisor continue to get buy-in from the franchisees?

Some social psychology research on social dilemmas suggests that the franchisor must be dominant and aggressive to lead.

A social dilemma exists when we know that if some us coordinated, we would be better off. But, we also know that most us think that not enough of us will coordinate and so any benefit to coordination is at best illusory and perhaps a trap. So, some argue, we need to be forced, coerced or bullied into joining.

Groups need to be lead by a dominant and assertive leader in order for the benefit of coordination to be real & exist, is the claim.

Robert Livingston and many others argue for this conclusion, lending support to benevolent dictator picture of a franchisor founder.

"Being kind and self-sacrificing will get you plenty of friends, but won't help you win a corner office", argues management professor Robert Livingston.

The altruistic are typically seen as good people, but not dominant and aggressive enough to lead, Livingston's research shows.

"On the one hand, generous individuals are admired," he says.

"On the other hand, they may be perceived as feeble 'bleeding hearts' who lack the guts to make tough decisions.

And, we need dominant and aggressive leaders because:

In social dilemmas "when groups had to compete against each other, dominant individuals rose to the top while benevolent people were least likely to be elected."

(It is well worth listening to Livingston explain his theory of leadership in more detail.)

On the other hand, Tom Schelling explained, almost 35 years ago, the solution to a social dilemma didn't need a certain personality type. The solution required the existence of a group disciplined enough that, even though resentful of free-riders, its discipline could be profitable for the group (though even more profitable for those who stayed out.)

A combination of discipline but resentment. Not altruism, not dominance, but a combination of discipline with a type of resentment focused on the free riders would stop the group from unraveling.

How can we decide between Schelling and Livingston? One idea is to use a negotiation training exercise & a variety of social dilemmas to record people's emotional & immediate responses.

Trainers in leadership have been using social dilemma exercises to produce various "Aha" moments, for quite some time.

One such exercise is called "Win as Much as You Can".

What is Next?

I want to step through an analytic discussion of the Win as Much as You Can exercise. (Only by playing it with real people can you get the experiential content. In most cases, the group fails to coordinate, and remains in the state of nature - and more so with dominant and aggressive leaders!)

Then, I am going to suggest an alternative exercise and provide reasons why, if Schelling is right, this new exercise should provide an "Aha" moment about how discipline and resentment can hold a group together.

In what follows, there will be -for some too much- use of calculation, simple graphs and decision theory. So let me give away the conclusion quickly -right after the description of the game.

Win as Much as You Can Game.

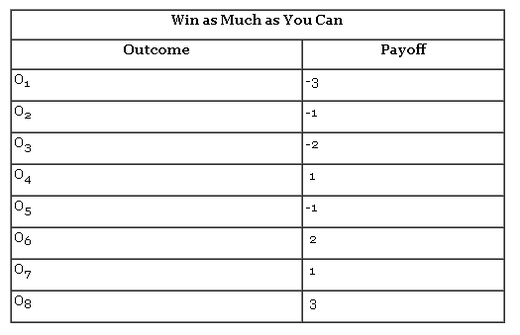

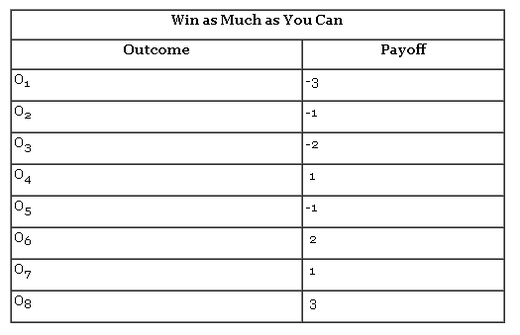

You and three others each have two choices, play Red or Blue, R or B. What each of you gets depends on what the others play and your choice, according to this table.

Group Individuals

4 Reds - Red player gets -1.

3 R, 1 B - Red players gets 1, Blue Player -3.

2 R, 2B - Red players get 2, Blue Players -2.

1R, 3B - Red player gets 3, Blue Players -1.

4 Blues - Blue Players get 1.

If this game is played, say for ten rounds, each player by playing only B, could win 10. Yet, in the thousands of exercises trainers have completed, almost no one or group gets to this outcome. (In most exercises, there are two bonus rounds, which simply complicates the scoring for no good theoretical reason.)

The group coordination of 4B's almost never happens. Even if it was expected, then some expect others to cheat and play R, and so they would play R first to "protect" themselves against the cheaters they have become.

Self fulfilling prophecies are at the heart of many a bad decision in which we start to expect the other person to act in a way contrary to our wishes - "seeing" them this way makes it more likely that they see us as acting contrary to some of their wishes. And so it goes.

But not always, and that is a bit curious. Schelling's insight was: not all of us, at the same time, have to see everyone else as a possible threat which unravels the group's coordination.

Is Schelling right?

Here is what I will show. If he is, then by changing the (1R, 3B) payoff to Red player gets 3, Blue Players get 0, two things should happen.

First, more groups should have higher scores in the modified Win as Much as You Can Game.

Second, the subgroup of 3 Blue players that coordinates should experience both discipline and resentment, but not enough resentment to unravel the group.

By coordinating, the 3B players can lift themselves out of the state of nature, in which they all receive -1, to 0, for a gain of 1, but the R free-rider gains 3. Note, Schelling is not saying that this subgroup has to form, only that if a subgroup does, it will be this one.

And if it stays together, discipline and resentment will run together. Discipline need to stick together and resentment against the free-rider, who plays R.

(If you are a trainer, you can run both exercises, report back - all without having to do any of the calculations, which follow below.)

Justification for the Change in Payoffs

For the intellectually curious, we push on.

It seems unlikely that the group will play 4 B's together. Further, if one person should correctly forecast that the group was leaning to 4 B's, it would be in their interest to act as if they were going to play B, just in order to play R at the last possible moment. Much like a good poker player bluffing the table.

If only one succeeds at this strategy - this success will invite mimics. Soon the coordinated strategy of 4 Bs will completely unravel.

The remainder of this article will provide reasons justifying why the small change in the original game should bring about some subgroup coordination.

1. Transforming the Win as Much as You Can Exercise into a several Multi-Person Prisoner's Dilemma Game.

First, we will take some time to show that the Win as Much as You Can game is a combination of several special social dilemmas, Schelling called these "Multi-Person Prisoner's Dilemmas", or MPDs.

A prisoner's dilemma is a social dilemma in which the unraveling is caused by enough people reasoning using a principle from decision theory: If no matter what everyone else does, I would be better off choosing R over B, I should always chose R.

There is much to be said for this rule. Some have elevated it to a canon of rationality. If others disagree with the rule, then when it is available, their decisions make those who follow the rule better off.

The well-known problem with the rule is that its use in a multi person prisoner's dilemma produces dismal results.

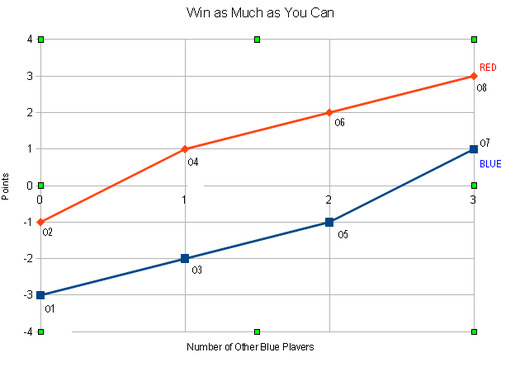

(A word is needed about the diagrams that follow. I usually make mistakes drawing them - especially when I "know" how they should turn out. To avoid making mistakes, I have created a checklist or algorithm, which helps me. For those more talented than I, this checklist will be too tedious. However, for you and I, I believe it to be helpful.)

The Payoff Algorithm

Step 1. Identify the choices and individual can make, R or B.

Step 2. Identify the outcome the group can arrive at, counting each outcome as distinct based upon whether the individual played R or B.

Only Step 2 needs an illustration. Consider the pattern 3R, 1B. This is two outcomes - if you played Red, the outcome is 1, while if you played Blue, the outcome is -3.

Step 3. Count the outcomes in a systemic manner and plot.

There are eight outcomes in this case and not 10 because 2 patterns 4R and 4B have only one outcome, while all the other patterns have two outcomes.

How should we label these eight outcomes?

One way is to pick a variable k, running from 0 to 3, where k is the number of other individuals playing B. The outcome O2k+1 is the outcome where you play B and k other individuals also play B. The outcome O2k+2 is the outcome where you play R and k other individuals play B.

The outcomes range from O1 to O8.

O1 is the outcome where k=0, nobody else plays B, but you do. The payoff to the B player if the pattern is (3B, 1R) is -3.

O2 is the outcome where k=0, nobody else play B, and neither do you. The pay off to the R player if the pattern is 4R is -1.

For, k=1, 2k+1 =3 and 2k+2=4.

O3 is the outcome in which one person plays B, and so do you. The payoff to the B player if the pattern is (2B, 2R) is -2.

O4 is the outcome in which one person plays B, and you don't. The payoff to the R player if the pattern is (1B,3R) is 1.

Let's summarize all of the outcomes.

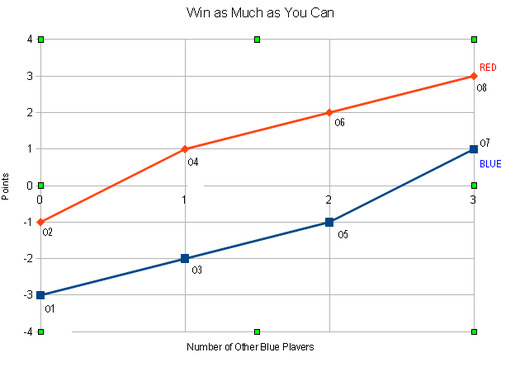

We can now draw a diagram, with k on the X axis, and the Y axis reflecting the payoffs of B and R, given k people have chosen already to play B.

There are two easy things to read off the graph. (This is not a single MPD because the lines are not straight.)

1. Red dominates Blue - for no k, or group of individuals, would be better to be part of the k group of B players. For each k, you are better off being a R.

2. But O2, 4R, is a bad place for everyone compared to O7, 4B.

(For those wondering if this hasn't been a lot of work to recover some obvious points, there had better be a reward for making it this far!)

The reward is to focus on O5, and the horizontal line we can draw from O2 - the state of nature. The horizontal line is the payoff in the state of nature, any outcome above that -short of complete group coordination- is a group whose discipline is both profitable to join, yet profitable to leave.

The outcome O5 or the pattern (3B, 1R) has a payoff of -1, but is tantalizing close to the optimum 4B, O7.

If 3 players played B, how much harder would it be to get the last person on board?

In this case, it should be very hard. For the R player, the pattern in O5 is the outcome O8 - how can you persuade him or her to accept 1 instead of 3?

Thus, if three players can coordinate their actions by playing B, their payoff isn't greater than the state of nature, O2. Partial coordination doesn't pay and it doesn't make it more likely that full coordination is reached. Two players cannot do any better.

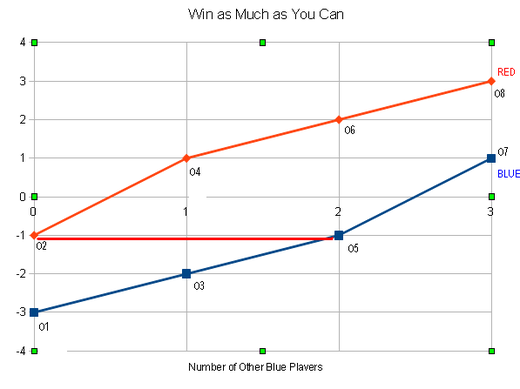

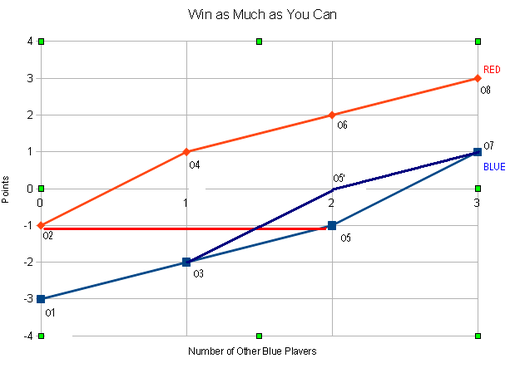

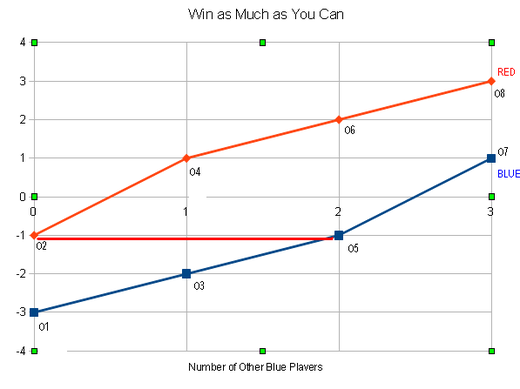

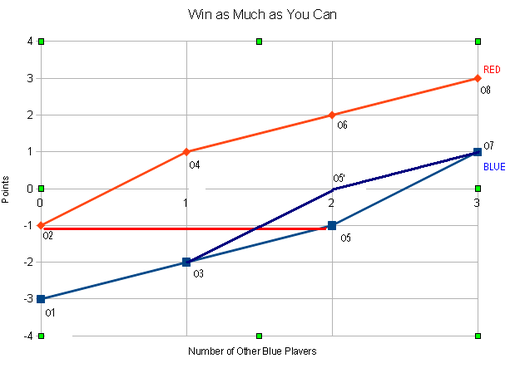

But, what does the diagram look like if we change O5? Let's just move it above the horizontal line and give the B players 0 instead of -1, at O5'.

Now, the coalition of 3B in this new game satisfies Schelling's criterion:

"The smallest disciplined group that though resentful of free-riders can be profitable for those who join (though more profitable for those who stay out)."

Is it true? Can this simple change in pay-offs actually make a difference or is this a theoretical possibility only? What do you think will happen if this training exercise is played with both games instead of just the standard game?

We need to try it and see if Schelling's analysis bears fruit.

Did you like this? Why not click here and subscribe to Webster's Strategic Stories.

Your friends and competitors are already reading and learning more business strategy. Why not you?

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f227fe93-0bae-4864-b9ac-313d19b61b46)