Throughout the United States franchisors have been able to enforce choice of law and venue selection provisions in their franchise agreements with few exceptions. A few states have proactively limited venue selection, but in the absence of rule or statute the U S Supreme Court has exonerated venue selection in the franchisor's home state as reasonable (Burger King leading case). On the issue of choice of law the primary confrontations have been over post termination covenants not to compete.

One state, California, prohibits them by statute (but see the Schlotzky's case where the California court permitted a restriction against making the Schlotzsky sandwich that was held to have secondary meaning as a source identifier for Schlotzskys).

Elsewhere when a franchisor chose its own state as the choice of law and the law of its home state was more permissive about use of post termination restrictive covenants, the question was whether the more expansive permitted use infringed the public policy of the franchisee's state. In those instances courts customarily reduce the scope of the covenant to the point at which the confrontation with public policy is eliminated.

The current direction of the law on post termination restrictive covenants, except in California, is simply to enforce them. The franchise can be old to the point of moribund and the market can already be so flooded with direct competition that enforcement of the covenant really bestows no material benefit to the franchisor other than a vendetta interest. Competent drafting of restrictive clauses today usually tie the clause in with the protection of confidential information and the non disclosure clause.

Venue selection has received little attention except for the rare prohibitory statute or rule.

Most large franchisors have now expanded extensively into foreign markets. Many of them still keep the domestic venue selection clause that facially requires franchisees in foreign countries to come to the United States and litigate or arbitrate disputes in the franchisor's home town. Just such a situation arises now in the context of an American franchisor requiring its European Community franchisees to resolve disputes here in America.

The agreement also prevents class treatment of disputes and groups as joint complainants. The EU franchisees would have to come to America one at a time and hire a USA lawyer to have their disputes sorted out by a court or arbitrator.

In the situation of poorly performing franchise systems, the franchisees' position is that this makes dispute resolution effectively unavailable to EU franchisees. This is, to be certain, part the purpose of this contractual configuration. This article offers a road map through the issues that will have to be dealt with if EU franchisees decided to attempt to defeat the USA venue selection clause.

INHERENT PRO FRANCHISOR BIAS IN THE USA

Over the last 25 years franchise law produced from decisions in dispute resolution has become more and more favorable to franchisors. Part of the reason for this tectonic shift may be attributed to the fact that every time a major court resolves a significant issue in favor of a franchisee, lawyers representing franchisor groups immediately redraft applicable franchise agreement provisions to circumvent that ruling. The "draft around" exercise has paid off handsomely for franchisors, and one would indeed be foolish not to avail itself of that technique. That is one reason lawyers go to annual seminars where they receive the benefit of the shrewd draftsmanship of the industry's best and brightest nit pickers. There is actual biblical precedent for this, but that is better left for drinking parties.

For these reasons alone, EU franchisees would win a substantial tactical and perhaps strategic advantage if they first found a way to defeat the international venue selection clause and were then able to have their disputes with their franchisors resolved in their own courts and arbitration resources, in their own languages and in context of the fairness balancing influences of their own countries and cultures.

Inasmuch as there is now no significant history of franchise litigation in EU countries, there is an opportunity for EU courts to approach franchising issues free of the pro franchisor bias so pervasive in the USA. How might one go about accomplishing that What are the issues and salient fact patterns relevant to confrontation of international venue selection provisions

THE ISSUES AND THE FACT PATTERNS

In the USA the ruling case law is that a franchisor may compel dispute resolution in its home jurisdiction under the law of its home jurisdiction. That is long established law. The rationale is that the franchisor ought to be able to operate its system in accordance with one set of legal principles and requirements and avoid the vagaries of local law that on the whole provide no significantly better legal climate than the law of the franchisor's home jurisdiction.

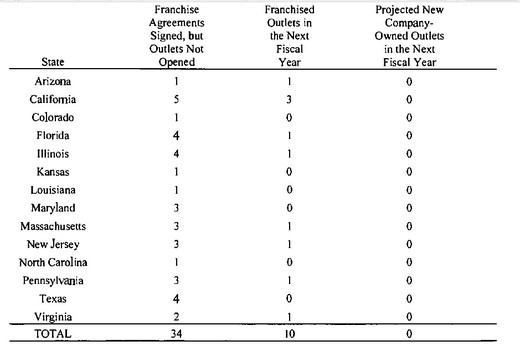

Even in this system, franchisors are required to provide a section of their disclosure package (FDD) that deals with state specific law that may affect the enforceability of various provisions of the franchise agreement. The shibboleth is that the essence of uniformity lies in its variables. There is essential uniformity, but not absolute uniformity from state to state.

Recognizing that the International Franchise Association spends a fortune every year to lobby franchisor favorable positions in every jurisdiction, nationally and internationally, one must begin by acquiring command of the jurisdictional trends and precedents in the EU countries relating to franchising dispute management to ascertain the extent to which there remains a meaningful opportunity to defeat an international venue selection provision under any circumstances at all. This involves the EU itself and the individual member states.

If the matter remains unsettled, then where does one initiate a proceeding seeking to upset a particular venue selection provision One thing is certain. One does not go to any USA court to try to achieve this.

It would be a total waste of resources with an almost guaranteed adverse result. This may mean a race to raise the question first, as one tribunal might not wish to devote its resources to an important question that is already before another tribunal. If the first tribunal decides the issue in a manner and pursuant to a rationale with which the EU tribunal would be comfortable, the ability to seek consideration of the matter before a potentially more sympathetic body is simply lost.

For this reason, I am somewhat surprised that USA court determination of these issues has not already been sought by the USA franchising community via declaratory judgment actions in American courts. By the time this article circulates, that tactic may be initiated as a possible means to preempt EU rulings on it. L'audace! L'audace! Toujours l'audace!

The salient fact issues will be distance, language, economic preclusion of a right to fair adjudication and the equities of the particular fact pattern before the court. It will be essential that the franchisee(s) in the case be essentially compliant even though contentious. You don't take a scoundrel to a court seeking fairness and equity.

If the initiator is a group of franchisees, it would be worthwhile to screen out the bad apples and proceed on behalf only of the more platinum plaintiffs/complainants. How that screening is accomplished is a subject for a totally separate article all by itself. Underlying every technical decision is an inherent, even though unspoken, issue of whether the party seeking relief is deserving of the relief.

With respect to the issue of distance, be mindful that a venue selection clause in an American franchise agreement may impose a more than 3,000 mile distance disadvantage, and that has not been the basis of an unreasonability ruling in a USA court. Distance from the EU to the east coast of the USA may not be much more than that. For this reason one should never raise the distance issue in isolation, but in every case in combination with language and other issues.

Consideration should be sought in light of the fact that the USA franchisor does not deem it inconvenient in any economic or distance sense to franchise its business in the EU as well as comply with EU and member state laws and regulations applicable to franchising there.

The distance and language issues should always be raised in combination with the franchisor's willingness to subject itself to EU and member state laws that enable and permit the enterprise from which the franchisor derives substantial financial benefit. That will go a long way toward blunting franchisor arguments before a European tribunal but probably not here in America.

The other crucial fulcrum of decision in this project will be the economic argument (which also would not prevail in the USA.) In the USA the concept of business risk, its assumption when you buy a franchise, not being a child or other person in need of special attention and protection in any business to business transaction tend to foreclose sympathy for "the downtrodden" in the sense of poor unprofitable franchise owners.

These so called victims, when applying to purchase the franchise, portrayed themselves to be financially and experientially capable of accepting the risks. Moreover, there are competent pre-investment due diligence assistance resources if they are not themselves astute at small business investment vetting. Additionally, the fact that the franchise agreements are in every instance rather draconian does not affect the pitch of the playing field in this discussion.

If you sign an agreement that permits the opposite party to take financial advantage of the situation and you do not expect that to happen, you are simply a fool. Actually, very few of these investors ever avail themselves of really competent pre-investment due diligence assistance at a meaningful level of competence simply because the services are not cheap. But that is their choice freely made.

There are escape hatch clauses in every franchise agreement plus a pre closing escape hatch questionnaire that further disable claims of being taken advantage of even when they have been taken advantage of in many cases and know about that before they sign the agreement.

So in the USA the "Oh poor me" gambit is usually worthless. Whether EU or member state tribunals are more receptive to the "poor me" arguments than USA courts remains to be seen. Ultimately, the USA is absolutely the worst place in the world to try franchise fraud and abuse cases today. There is no downside to trying to escape to another jurisdiction for resolution of disputes.

What constitutes an actionable complaint is probably different in the USA than elsewhere also. Notions of good faith and fair dealing are litigated here every year, and every year courts seem to find ways to deny their application other than lip service. What we just yawn at here in the USA could be a major offense against any fairness concept under EU or member state law. Equitable considerations are essentially worthless in the USA in business to business disputes. The free market means just that - the wild west.

Where then is the touchstone combination of circumstances in the making of a competent economic/predation case for escaping a venue selection and a choice of law provision in a franchise contract between an American franchisor and an EU franchisee I suggest the following approach.

Take seriously into account that an American court would accord no significance to the fact that the franchisee(s) are from another country and use another language. There will be absolutely no respect for a position that is a function of nationality. EU franchisees should make that clear to the EU or member state tribunal and suggest that a USA franchisor not be accorded preferential treatment.

The contract will have been drafted in the USA and will be in English.

There will be a local language version, but in the event of a disparity of meaning in any provision there will probably be a clause that says the English language version rules.

The EU franchisees will have been at a decided disadvantage in almost every instance when the "deal" was originally made.

One should suggest to the tribunal that one of the purposes of the EU and member state commercial law structure includes taking into account every way in which the EU party may have been disadvantageously positioned and make compensation for that by at least placing disputes before an EU or member state tribunal and applying the law of the franchisee's home country.

THE ECONOMIC POSITIONS

Usually the situation at hand will involve franchisees who invested in a franchise opportunity upon the stated or obviously implied representation that the franchised business model was a proven business concept capable of being operated by an investor acceptable to the franchisor with a positive financial performance profile.

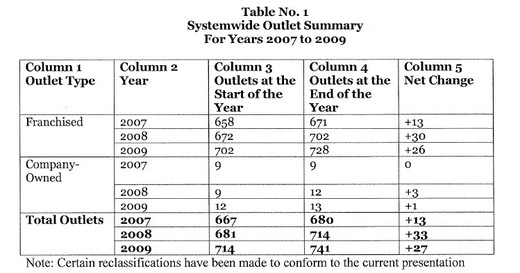

If it is the case that the franchisees in the EU country are, as a group, unable to succeed in the business as licensed, that should be strong evidence that the opportunity was not investment worthy for this country/market and that the franchisor had no business selling it in the EU. If it is also the case that the franchisees in the USA are not doing well, that should be considered a strengthening of the conclusion that the transaction was not investment worthy in the beginning, much as a court would deal with a security that was not investment worthy.

There is a duty in all jurisdictions relevant to this discussion that the seller disclose material information that would cause a potential investor to make a negative investment decision.

In the face of such evidence, the franchisor should never be allowed to impose upon the EU franchisees an obligation to submit disputes to an American dispute resolution resource. The franchisees will be economically preempted from obtaining justice as a matter of simple economics, and no company selling investments should ever be allowed to put a victimized investor to that disadvantage. The argument that this requires prejudgment of the ultimate issue does not meet logical criteria here because we would be litigating jurisdictional issues and the findings would be for that limited use only.

In the USA the same standard is used in deciding whether preliminary relief should be granted in the course of deciding the issue whether the party seeking relief has "a likelihood of ultimate success on the merits. Taking this approach in protecting EU franchisees would not be a departure from American legal standards, and because of that the American franchisor should have no grounds to complain.

There is a countervailing argument available to franchisors in this instance. Regardless where EU franchisees must litigate their disputes, they will have to come up with resources to hire competent counsel, very few of which in the USA will accept them as clients on a contingent fee arrangement. In the EU contingent fee arrangements are much less condoned than in the USA.

The same requirements exist in the USA, and the cost of really competent representation is not going to be that different than in the EU. Depositions can be held in the locales of the witnesses, eliminating travel of everyone internationally before there is actually a trial. In each event the franchisees will need to create a common fund to share litigation costs, so there is no venue difference on that issue.

The adverse economics issue must be presented in a logical connection to other important issues rather than as a stand alone basis for decision.

If in addition to such a scenario (or even without it for that matter) the EU franchisee(s) can make a case of post execution abuses that materially adversely impacted the ability of the franchisees to make a reasonable financial return, that alone should make out a case that the franchisor is perfectly willing to engage in predatory practices no matter the impact upon the franchisees. A comparison of the measurable relationship cost as stated in the FDD to the actual costs, including extraneous revenues from franchisee operations not quantifiable from the information provided in the FDD, should serve to show that a franchise portrayed in the FDD as having a relationship cost of 15 % of gross sales actually has a relationship cost of from 20% to 25%. That would be very strong evidence of predation by the franchisor. Ten to fifteen percent of gross sales usually will equate to a negative impact of from 30 % to 50% of net profit. That is more than substantial impact to justify an EU or member state tribunal refusing to enforce a venue/choice of law provision in a franchise agreement.

How one goes about preparing such a case and obtaining evidence of sufficient quality is not part of this article, as that will vary with each case. Suffice it to say that counsel with very extensive experience in preparing and trying lawsuits involving franchise fraud and abuse should be tasked with assisting EU counsel in the entire proceeding. Knowing the theories and the art of expressing the theories effectively will not suffice without a record of competent evidence to support them.

As always, you can call me, RIchard Solomon, at 281-584-0519.

For the 5 Most Fascinating Stories in Franchising, a weekly report, click here & sign up.